Lake Saint-Pierre

A meeting with Guillaume Lafond, a young trapper from the Nicolet region, helped us understand how trapping has evolved over time. In modern times, humane traps are used; these traps kill animals very quickly (in about 30 seconds) to minimize their suffering.

The darker trap in this picture is a leg-hold trap made by the Victor Trap Company, hence the V on the pan. It is meant for use on the shore near water, and should be placed in such a way that trapped animals will swiftly drown. This type of trap should not be used on dry land, as the animal would be injured but remain alive, resulting in needless suffering. The other three traps are body-gripping traps of various sizes. The smallest one, attached to a chain, is intended for mink. The largest is used to trap raccoons. The long spike on the muskrat trap is used to anchor it to the ground in the middle of a muskrat run.

Guillaume shows us a fully set body grip trap. The chain is used to anchor the trap to a tree or to the ground, preventing it from being lost. Because mammals have a very keen sense of smell, the trap must be handled with gloves to avoid leaving odours.

A safety tool is used to make sure the trap does not spring shut on the trapper's hand. The tool is removed once the trap is set. The trap in the lower right-hand corner of the photograph is a leg-hold trap used to catch raccoons. Only the raccoon's paw will fit into the trap, which holds the animal's leg without injuring it. Traps must be checked on a regular basis, especially when they are set near towns, where they may catch domestic animals.

This leg-hold trap is buried so that only the opening can be seen, then baited with a marshmallow. When a raccoon reaches in to grab the bait, the jaws snap shut, trapping its paw.

Guillaume uses the skins of animals he has trapped in his presentations to young people. He likes to point out how each species is adapted to its diet and way of life. He also explains how humans use various different furs: coyote to line hoods, raccoon for hats and coats, beaver for gloves and boots, and fisher for hats. Otter fur is dense and glossy, and greatly prized on the market. This high quality fur is used to make coats.

Aboriginal people would stretch beaver pelts on an oval frame to dry them. This method is still in use today.

From the 16th century to the early the 19th century, beaver fur was in very high demand for making felt hats. Trapping was so intense that beaver populations eventually collapsed. The process of making a felt hat took around 7 hours of work and involved some 30 different steps. First the guard hairs were removed, leaving only the dense undercoat, made up of fine, silky hairs which could be felted. Beaver felt hats protected the wearer from sun and rain. They also served as status symbols, advertising the wealth of the people who wore them.

Guillaume keeps the skulls of some of the animals he traps to better understand their physical adaptations. Once he has satisfied his scientific curiosity, he communicates what he has learned about various animal species. His skull collection is a great tool for presenting information. By looking at the beaver's extremely long teeth, for example, it is easy to understand why beavers (and other rodents) have such a strong gnawing instinct, as their teeth never stop growing and need to be constantly worn down.

In early colonial times, French fur traders known as coureurs des bois would wear an arrowhead sash on their hunting expeditions. This emblematic finger-woven sash was worn over a trader's coat to keep it closed, but was also strong enough to pull heavy loads. In later times, the arrowhead sash became more fashionable than utilitarian, and was produced for the mass market. Dedicated crafters still make traditional arrowhead sashes today, tirelessly repeating the same intricate weaving motions practised by their ancestors.

Guillaume recently took a course to learn the secrets of making traditional arrowhead sashes. His interest in traditional activities and love of the outdoors are what originally led him to trapping. In winter, he checks his trap line on snowshoes, which make it easier to walk through the drifts. He sells the fur of the animals he traps, and occasionally eats beaver and muskrat flesh. He uses a combination of traditional and modern techniques.

These snowshoes, with their large surface area, were used to walk on deep snow without sinking. Although snowshoes are still used today, their appearance has changed dramatically.

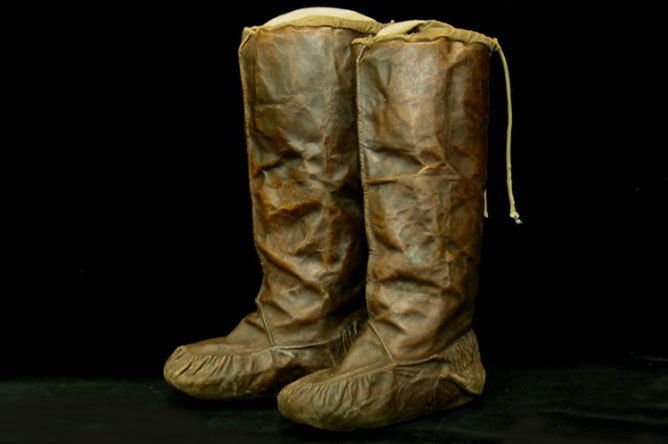

These boots from the 1850s were probably meant to be strapped into snowshoes.

The trapping season begins in late fall, continues through the winter, and ends in spring. Guillaume sets traps in farmland and forests not far from town. In this photo, he is setting a body-grip trap in a wooden box designed specifically for catching raccoons. The box is long enough to prevent the raccoon from reaching the bait with its paw. The animal must put its head in the box to reach the food. The body-grip trap is placed at the entrance to the box, with the springs poking out through slots in the sides.

Wildlife managers promote hunting and trapping to control animal populations. These activities are regulated to prevent wasteful use of resources and avoid unnecessary suffering.

For more information (in French only): Ministère du Développement durable, de l'Environnement, de la Faune et des Parcs: le piégeage au Québec

Hunters always keep a hunting knife handy; it is an essential tool.

Hunters once used powderhorns, made by capping both ends of a bull's horn, to keep their gunpowder dry.