Lake Saint-Pierre

In the early 18th century, the Abenaki settled on the shore of the Saint-François River, where they founded the village of Odanak. This community subsisted by hunting, fishing, gathering berries and practising agriculture. Both men and women would weave baskets out of ash and sweetgrass. Today, Abenaki elders proudly pass on their traditional techniques to younger generations, ensuring the continuity of the art of Abenaki basket weaving.

For more information (in French only): Virtual Exhibit La vannerie abénakise : d'hier à aujourd'hui

First, a black ash tree is felled and the bark removed. Then, the men pound the trunk with the back of their hatchets to separate the annual growth rings. Black ash is used because it is the only tree whose wood will separate in this way. The trunk must be humid, as this makes the wood more flexible and less likely to crack.

Once the rings have been separated, a cleaver is used to detach the splints, which are then finished using various instruments. The splints are planed to make them thinner, softer and more flexible without compromising their strength.

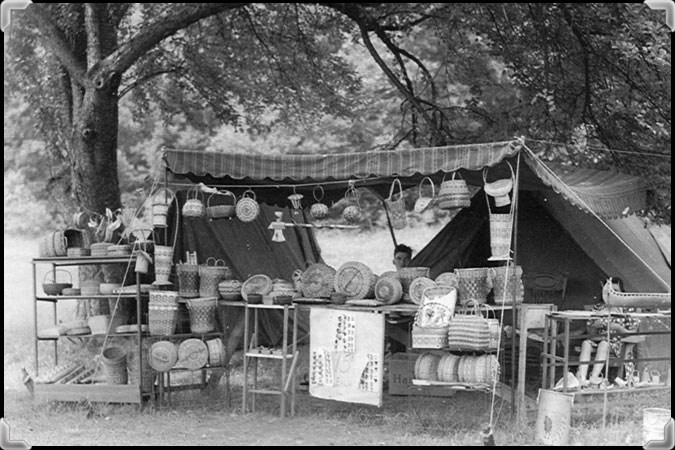

The Abenaki originally made baskets for purely utilitarian purposes. Starting around 1870, basket weaving became a local industry that persisted for seven decades.

From the late 19th century until the 1940s, Abenaki families would travel to resort areas in the United States to sell their wares. The many tourists that visited these locations represented a substantial market, which could bring in considerable revenue. The wide availability of plastics after World War II had a very negative impact on sales of traditional ash baskets.

Annette Nolett teaches her two granddaughters basic Abenaki basket weaving techniques. This attentive grandmother lovingly supervises their work.

To make a basket, the thin strips of ash need to be moistened slightly to make them more flexible and easier to work with.

Ash strips and ribbons can be dyed in a wide range of colours, adding a touch of whimsy to the objects produced. Thinner ribbons of ash are used to bind the thicker strips.

First, the weaver makes the base of the basket; then, strips are woven up to the top of the basket.

Each basket weaver has her own style and adds her own personal touches. Annette likes to add braids of sweetgrass to her crafts, while her granddaughter Angelica often includes motifs inspired by nature: flowers, butterflies and dragonflies.

Some baskets are ornamented with a woven sweetgrass handle and raised points that recall the spines of a porcupine. The points are created by folding an ash strip over itself.

Basket weavers use ash strips of various sizes, as well as molds, tools and sweetgrass, to produce their crafts.

Angelica Duane tells how she began to practice basket weaving a few years ago as a way to spend more time with her grandmother. By sharing this tradition with her two granddaughters, Annette Nolett is helping to ensure this ancestral art continues to be practised in the Abenaki community of Odanak.

Baskets of all shapes and sizes are the most frequently produced craft, but the weavers also make woven bookmarks and even pincushions with a woven ash base.

This photograph shows gauges lying on top of basket moulds. The blade of the gauge is used to divide splints into thinner strips, while the moulds are used to shape the baskets. These hand-made tools were invented by the Aboriginal peoples of North America.

Today, Abenaki woven crafts are considered true works of art and are much sought-after by collectors.